What is a Shell?

The shell is the command prompt within Linux where you can type commands. If you have logged into a machine over a network (using ssh or telnet) then you will in a shell. If you logged on to a Linux machine using a graphical interface then you will may need to open a terminal client to see the shell. There are several different terminal clients available such as xterm, konsole and lxterm, or it may be just named Terminal Emulator.

Windows users may be familiar with the concept of a command prompt, or DOS prompt, which looks similar to a UNIX shell. The UNIX shell has more features and is practically an entire programming language, although don’t let that put you off as you can use the shell without any programming ability. Even if you don’t “do programming” you may find that’s it’s worth learning a little bit of shell script programming as it can be used to make your life easier.

Often people seeing the shell will think that this is the UNIX / Linux operating system. It is in fact a program that is running on top of the operating system. To take a basic view of how Linux is built up see the diagram below:

The different layers of the Linux operating system

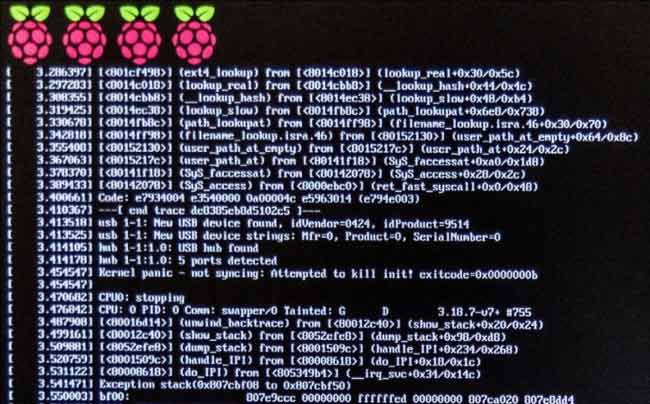

The kernel is the heart of the operating system. This is the bit that is actually Linux. The kernel is a process that runs continuously managing the computer. The kernel is a very specific task so to allow programs to communicate with it there are a number of low level utilities that provide an interface between the application and the kernel.

The shell is an application that allows users to communicate with the computer. It is a text based application that allows programs to be started and tasks to be run. The shell is within a collections of utilities known as GNU. Without the kernel the computer cannot run and without the GNU utilities it can’t do anything useful which is why the operating system is sometimes called GNU/Linux; although this ignores the host of other applications that are also included (for brevity I am just using Linux to mean everything included on the Linux distribution).

The Different Shells

In the same way that different variants of UNIX were developed there are also different variants of the shell.

Here’s a list of the most common UNIX shells:

| Name of shell | Command name | Description |

| Bourne shell | sh | The most basic shell available on all UNIX systems |

| Korn Shell | ksh / pdksh | Based on the Bourne shell with enhancements |

| C Shell | csh | Similar to the C programming language in syntax |

| Bash Shell | bash | Bourne Again Shell combines the advantages of the Korn Shell and the C Shell. The default on most Linux distributions. |

| tcsh | tcsh | Similar to the C Shell |

Common Linux / UNIX shells

When you login to a Linux machine (or open a shell window) you will normally be in the bash shell.

You can change shell temporarily by running the appropriate shell command. To change your shell for future logins then you can use the chsh command. This is normally setup to only allow you to change to one of the approved shells listed in the /etc/shells file. If you change your shell for future sessions this is stored in the /etc/passwd file.

The shell is more than just a way of typing commands. It can be used to stop, start, suspend programs and by writing script files it becomes a programming language in itself.

More details of the shells are listed below.

Bourne Shell – This is the oldest shell and as such is not as feature rich as many of the other shells. It’s feature set is sufficient for most programming needs however it does not have some of the user conveniences that are liked on the command line. There is no option to re-edit previous commands or to control background jobs. As the bourne shell is available on all UNIX systems it is often used for programming script files as it offers maximum portability between older UNIX machines. Bash is fully backwards compatible with the Bourne Shell so running the bourne shell on Linux will often call the bash shell (using a link between the files).

Korn Shell – This is based on the Bourne shell. One enhancement that is particularly useful is it’s command-line editing facility. It is possible using either vi or emacs keys to recall and edit previous commands. There are also more powerful programming constructs than the bourne shell, however these are not as portable to older machines. To run the Korn shell you can run either ksh or pdksh from the normal shell (assuming it is installed).

C Shell – The c shell syntax is taken from the C programming language. As such it is a useful tool for anyone familiar with programming C.

Bash Shell – The Bash shell is a combination of features from the Bourne Shell and the C Shell. It’s name comes from the Bourne Again SHell. It has a command-line editor that allows the use of the cursor keys in a more “user friendly” manner than the Korn shell. It also has a useful help facility allowing you to get a list of commands by typing the first few letters followed by the “TAB” key. It is the default shell on most Linux distributions and unless otherwise specified is the shell used for the future examples.

tcsh – This is a different shell that emulates the C Shell. It has a number of enhancements and further features even than the bash shell.

The Shell Prompt

When logged into the shell you will normal see one of the following prompts: $, % or #. This is an indication that the shell is waiting for an input from the user. The prompts can be customised but generally the last character should be left as the default prompt character as it helps to indicate which shell you are running and whether or not you are logged in as root.

The Bourne, Korn, and Bash shells all accept a similar syntax. Unless you are using one of the advanced features you do not necessarily need to know which one of them you are in. If however you are in the C or tcsh shells this uses a completely different syntax and can require commands to be entered differently. To make it a little easier these have two different prompts depending upon the shell.

The default prompts are:

$ – Bourne, Korn and Bash Shells

% – C Shell

When logged into the computer as root, the user should take great care over the commands that are entered (further information about the root user is included in the System Administrator book). If you enter something incorrectly you could end up damaging the Linux installation files or even delete all the data from a disk. For this reason the prompt is different when logged in as a root user as a constant reminder of the risks.

The default prompt for root is the hash sign # this is regardless of the shell being used.

Login Settings for the Bash Shell

When you login to a shell a number of variables and settings are configured for your shell. The files that are most commonly used by bash are:

/etc/profile

~/.bash_profile

~/.bashrc

~/.bash_logout

These files are text based shell scripts that can be used to define settings for either system wide settings (those in the /etc directory), or for an individual user (those in the users home directory specified by ~). Different files are called depending upon whether it is an interactive login shell or a non-interactive shell.

Bash as an Internactive Login Shell

The following is followed if bash is invoked as an interactive login shell, or as a non-interactive shell with the –login option.

First the shell reads and executes commands from the file ‘/etc/profile’, if that file exists. After reading that file, it looks for ‘~/.bash_profile’. If this is not found then it can instead use ‘~/.bash_login’, or ‘~/.profile’. The `–noprofile’ option may be used when the shell is started to inhibit this behavior.

The .bash_profile file is normally configured so that it also calls the ~/.bashrc file (if it exists) towards the end of the .bash_profile.

When the login shell exits, Bash reads and executes commands from the file `~/.bash_logout’, if it exists.

Bash as an Interactive Non-Login Shell

The following is followed when an interactive shell that is not a login shell is started (e.g. if switching user or launching from inside a shell). Bash reads and executes commands from ‘~/.bashrc’, if that file exists. This may be inhibited by using the `–norc’ option. The `–rcfile file’ option will force Bash to read and execute commands from file instead of `~/.bashrc’.

Bash as a Non-Interactive Shell

If bash is run as a non-interactive shell then the scripts are not called, unless the –login option is used. If there is a script given in the BASH_ENV variable then this will be run.

Normally the PATH variable is not set for any non-interactive shells so when running tasks in a non-interactive shell commands should be called using their full path names.

/etc/profile

The /etc/profile file provides the system wide default environment variables. Typically this sets up the umask, LOGNAME, and mail directories etc. It can also be used to change the default command search path (PATH) for all users on the system. As most systems don’t have a /etc/bashrc file aliases are sometimes included in the /etc/profile file.

~/.bash_profile

This provides the user specific environment variables, and is often used to add local search paths onto the PATH. This is called after the /etc/profile script.

~/.bashrc

This file is called for non-interactive shells, and is normally called from the ~/.bash_profile for interactive shells. It is normally used for setting up aliases and any other commands that are run during the startup.

~/.bash_logout

The ~/.bash_logout script is called when the user logs out of the interactive shell.

History

It is possible to recall previous commands by using the cursor keys, however it is also possible using the history command.

Issuing the history command will show the commands previously entered, you may want to pipe this through tail to just see the most recent.

$ history | tail

50 cd $HOME

51 pwd

52 clear

53 ls

54 cd test

55 ls

56 pwd

57 cd ..

58 vi temp.txt

59 history

$

to recall one of the commands listed enter an r followed by the number

r 55

The history is held in a file in the environment variable $HISTFILE. For bash this is normally $HOME/.bash_history.

Further Reading

For more information see the man pages or the Bash Reference Manual